Resilience: A New Grief Myth That Can Hurt You

The antidote to despair is not to be found in the brave attempt to cheer ourselves up with happy abstracts, but in paying profound and courageous attention to the body and the breath. … To see and experience despair fully in our body is to begin to see it as a necessary, seasonal visitation and the first step in letting it have its own life, neither holding it nor moving it on before its time.— David Whyte, Consolations

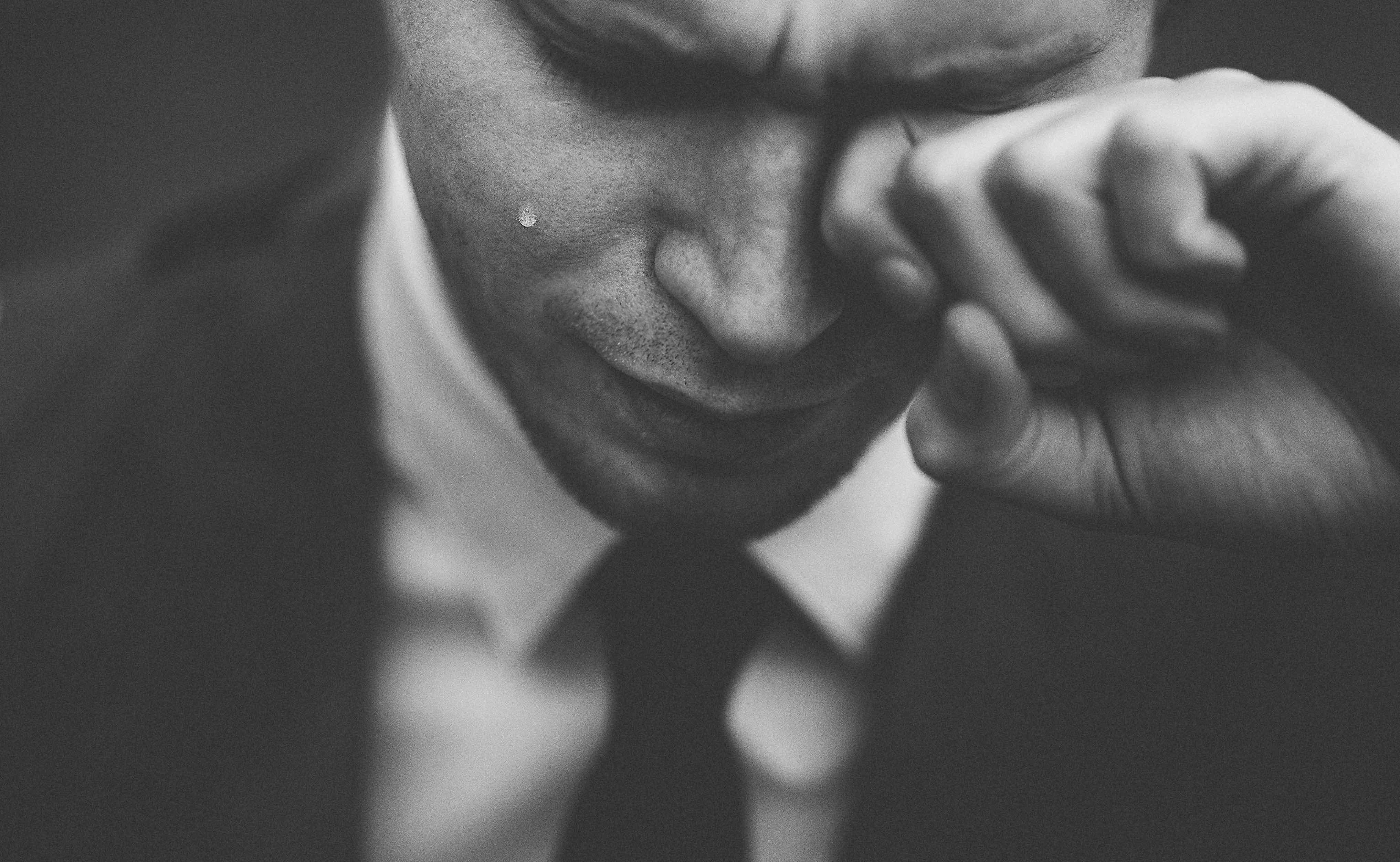

I had a hard time sleeping last week. I jolted awake with my heart pounding two or three times every night. Lying with eyes wide open in the dark, images of resilience tapped into a deep, old trauma.

Resilience was setting off trauma? Isn’t that weird?

Let me explain.

Last week I read Option B: Facing Adversity, Building Resilience, and Finding Joy by Sheryl Sandberg and Adam Grant.

Two years ago, Sandberg, the COO of Facebook, lost her 47-year-old husband to sudden death, and became a widowed mother to her two young children. Her experience led her to write about “kicking the shit out of Option B” when Option A (e.g., the dead husband) isn’t available. Grant is an organizational psychologist who applies to grief his cognitive behavioral strategies for changing the way one thinks during hard times — strategies he uses to help businesses rebound after financial setbacks.

Sandberg and Grant’s message for making it through grief centers on the concept of resilience, which they define as “the strength and speed of our response to adversity.” The goal of the strategies they offer is to help people bounce back to normal as quickly as possible.

Different Paths Through Grief

Sandberg is clearly a loving mother who wants more than anything to make sure her kids survive their tragedy intact and happy.

I identify wholeheartedly: When I was suddenly widowed at the age of 30 and my son was an 11-month-old nursing infant, the only reason I got out of bed in the morning was to keep my son alive and to try to make some semblance of a normal life for him.

But clearly, even though Sheryl Sandberg and I share an almost panicky desire to assure an ultimate post-death wellbeing for our children, we have very different philosophies about how parents need to deal with their own grief in order to help children thrive in the face of loss.

Sandberg is a living example of getting back to normal quickly. She’s a high achiever who applies her high-achieving nature to grief. Adam Grant’s tips for “overcoming” sadness and guilt, and for plunging into a full-out plan for finding joy resonated with her, and she applies those strategies with fervor.

In fact, 22.5 weeks into her widowhood, she decided to stop journaling because she consciously chose to try to “move on from this phase of my mourning.” She said, “I am pushing myself to move onward and upward — and part of that is to stop writing this journal.”

Then, fewer than two years after her husband’s death, she somehow found the energy to not only parent her children alone and be back at work, but also to write a book, pose for publicity photos in which she looks radiant, and go on book tour doing interviews all over the country.

Twenty-five years ago, I responded to my widowhood differently. I had a different kind of support and a different personality.

Within a culture that wanted me to hurry up and return to “normal,” I was fortunate enough to have family and a fearless therapist who insteadencouraged me to feel whatever I needed to feel for as long as I needed to feel it, and to allow happiness to make its slow and natural way back into my life over time.

They didn’t rush me back normal or push me to strive toward joy.

“Normal” had been irrevocably destroyed, and joy was an insult.

Though I was also a high achiever in life, I trusted that what was best for my son was for me to follow my instinct to allow the experience of being a widowed mother of a young child to humble me into slogging slowly, almost imperceptibly at times, through my days and through my healing

22.5 weeks into my widowhood, I was nowhere near finished journaling. I was still wading through a thick fog of pain with no vision of moving beyondanything.

My journal entries from that time were like this: “Everything hurts. Even though it was fun to go out to lunch with my friend today, I still had that weight on my heart. Everything is still colored by my loss. Everything is still flat and gray because my pain is always there. It might not be as intense as frequently as it was before, but it is ALWAYS there. I will miss you forever, Marty. You were the love of my life, and part of me died with you. I will never be the same.”

In the second year after Marty died, I was still reeling with pain and seething with anger at the universe for the destruction of my baby’s childhood.

I still had to scrape together every residual droplet of energy I could muster to pack a snack bag and take my toddler to the park. My skin was still a funny grayish color; my hair looked dry and shriveled; and I’d cracked three teeth from grinding them while I slept. I would never have been able to write a book or leave my kid to go on book tour. Publicity photos would have hideously revealed my suffering.

Yet in my vulnerability and pain, I was stronger than I’d ever been:

- To be utterly shattered yet to painstakingly build a new unchosen identity over time.

- To simply remain alive to do daily tasks and never give up under the weight of so much anguish.

- To push the boulder of misery off my chest every morning so that I could greet my giggling baby with smiles, even as the happiness tore my guts out and pushed tears down my cheeks because I couldn’t share his giggles with his dead father.

- To lie on the sofa when I had a 102 degree fever and sing Itsy Bitsy Spiderwhile my baby played on the floor next to me, and to change his diaper and make his dinner while the fever made me feel like throwing up (because my parents had to work full-time in another city and couldn’t help me, and none of my friends would risk getting my flu germs).

Every moment of every day required more courage and humility than I had ever known.

Indeed, over time, a visceral strength and appreciation of life emerged from my years-long trial by fire. To pay forward the privilege of support I received for enduring that long trial, I became a therapist.

For the last 20 years, I have dedicated my life to helping others make it through these kinds of difficulties; to advocating for the right of anyone who is suffering to take the long, slow, difficult time required to grieve and rebuild a life even as they continue to function, work, and raise children; and to studying the qualities of humanity that help us thrive after trauma so that I can reassure people with believable consolation during devastation.

Resilience Implies that Grief is Dangerous. Science Shows Otherwise.

From the core of awful strength and beauty that resulted from the rebuilding of my self from the shattered-ground-up is where the concept of resilience touches into my past trauma. On the surface, building resilience to make it through tough times seems like a good idea. But there’s a shadow side to it.

Throughout their book, Sandberg and Grant use terms like overcome adversity, triumph over sadness, recover from grief, regain control, build resilience, find joy.

Even though this perspective has helped Ms. Sandberg bear the unbearable, these terms set my teeth on edge.

Why?

Because I find every one of them subtly disempowering and potentially shaming for regular people experiencing normal grief reactions.

Stephen Porges is a scientist who describes what happens in our bodies and nervous systems when bad things happen to us. He talks about how when something traumatic happens to us (like suddenly and unexpectedly losing a loved one), our bodies and our emotional selves perceive danger.

When the nervous system perceives intense danger like this, it naturally generates extreme and chaotic-feeling fight/flight and shutting-down physical and emotional reactions as protections against danger. When our bodies and emotions swing wildly out of control like this, our brains respond by developing stories to make sense of what’s happening to us.

When our reactions are distressing like this and they occur in a society that judges and denigrates long-lasting and intense grief responses, the stories we create are often self-judging: “Something’s wrong with me. I need to make this stop.” “If I were resilient, I wouldn’t be so overwhelmed.” Friends and family — also frightened by the intensity of the distress they’re witnessing — can align with these invalidating stories, and perpetuate the fear of grief and its aftermath.

Dr. Porges’ theory leads to a more empowering, normalizing story:

Multiple aspects of loss such as sudden, permanent absence of a loved one that generates overwhelming distress; feared-to-be-unbearable emotions we can’t control; and extreme physical symptoms bombard our environment with signals of danger.

No matter who we are or how much support we have, when our bodies and emotions are pelted with these external and internal cues that shout danger,the intense physical and emotional reactions we see in grief naturally arise to help us survive in the newly dangerous territory. These grief reactions are not only “appropriate,” but are intelligent and protective under the circumstances.

Rather than self-judging, we can be self-reassuring, telling ourselves the truth that, “These grief reactions are actually my body taking care of itself in a situation fraught with danger. I can learn to work with these feelings so that they can guide me to safety and healing.”

A story like this one that normalizes, and even expresses appreciation for, our bodily and emotional wisdom within chaos offers encouragement for us to realize that even though what’s going on looks really messy, we’re in the right place. We just need support to bear the intensity.

Words Matter

In the face of grief, then, terms like resilience, overcome, recover, and control counterintuitively reveal a disempowering underlying story that perpetuates fear of grief itself.

- Resilience means a strong and speedy return to the original form after being bent or compressed.

- Overcome means to get the better of in a struggle or conflict; to defeat; to prevail over.

- Recover means to get back, to regain; its root means to get again.

- Control means to maintain influence or authority over.

All of these terms suggest that grief is a monster in the darkness that we should fear and flee from, or battle and fight against so that we will ultimately prevail over it to regain control.

Though ultimately fear-based, this ego-driven, battle-filled story preserves the illusion that even in the face of the most horrific tragedy, we can learn the tricks of resilience in order to dominate the grief monster and bounce back to normal in just over a year.

However, along with Dr. Porges’ work, emotion science and age-old human wisdom show that grief itself is adaptive. Loss is an injury to the psyche, to the soul. Though painful, grief is actually the brain/body/soul’s natural, necessary, healthy response to this universal wound.

That is, grief, as painful as it is, naturally arises in us precisely because the inevitable wound of loss is so great. We couldn’t survive this unavoidable wound without the healing force of grief.

Just as a wound to the body automatically — without any thought or effort on our part — sets itself to healing via a rush of blood that clears out damaged and dead cells, and a release of growth factors that spawn generation of new tissue, the spontaneous emotions of grief rush in to set healing in motion. Grief reactions are the natural yet anguishing growth factors that invite the deepest self to heal and to grow into a scarred yet more mature identity

So to believe the story that grief is a dangerous force that needs to be overcome is to actively fight against or to shut down the healing forces that our bodies naturally provide for us.

To try to bounce back to our old ways of being is to refuse to accept that there is no going back as much as we’d like to, and to turn away from the pain that comes from radical growth that’s being forced upon us whether we want to face it or not.

Instead of terms like terms like resilience, overcome, recover, and control; the terms fortitude, bear-with-courage, transform, and humility underlie a story that honors the strength of what it’s like to fall apart, completely rebuild against our will, and go on anyway; to go down and through the darkened way with help, trusting that it is the path to healing from the root of the soul.

- Fortitude means mental and emotional strength in facing difficulty, adversity, or danger, especially over a long period.

- Bear means to carry and endure.

- Courage means the ability to do something that frightens you; and mental or moral strength to persevere and withstand danger, fear, or difficulty.

- Transform means to make a thorough or dramatic change in the form, appearance, or character of.

These words tell the encouraging story of down-and-through, where messiness and pain are seen as part of the natural healing forces of grief — forces we need help and encouragement to bear with courage and fortitude over time, rather than to flee from or vanquish.

Hence the fortitude we are expressing (not building, but simply expressing) — just by getting out of bed and going to work and tending the children — is something that should be respected and honored.

Continuing to live with nothing more to give than hanging on by our fingernails should be seen as an expression of courage and strength.

Learning that we have control over much less than we ever thought makes us humble and teachable.

And viscerally understanding that nothing in life is guaranteed naturally unleashes gratitude.

Needing Help is Normal

This healing journey through the darkness is long and hard and at times unbearable. So we need help.

- We need support from loved ones and community to reassure us they will be with us as long as it takes.

- We need the patience and regard of the people around us.

- We need time to slow down, not a push to hurry.

- We need to know that it’s okay to distract ourselves from the pain when it becomes too much, not because the pain is damaging, but so that we can regain energy for facing it again when we feel stronger.

- We need to know that we are respected for being strong for living even as we’re falling apart.

Resilience as a Grief Myth Hurts People

I feel protective of the vulnerable, strong, fortitudinous self I was 25 years ago, when many people in my community were in a hurry for me to get back to normal while I was in the throes of crawling through the aftermath of my loss.

In addition to grieving, I had to defend against all the cultural messages that pushed me to leap over the long dark path and into the light, instead of honoring my long-lasting messiness and anguish.

I feel protective of all the grieving and traumatized therapy clients I’ve counseled over the past 20 years who have come to me feeling crazy, ashamed, isolated, and scared when their grief doesn’t conform to grief myths perpetuated by our death-averse society.

Popular grief myths — about stages of grief; about closure and acceptance; about how grief takes a year; about therapy being for grief gone wrong — hurt countless people every day.

I’m worried that the 21st century bandwagon of resilience is becoming a new hurtful grief myth that grievers will have to fight against in order to heal; a myth that will make grievers feel ashamed, crazy, and isolated if they cannot quickly bounce back, if they cannot return to a self they once were, if they cannot strive toward joy when they are slogging through.

Yet in truth, grievers who cannot accomplish these feats are normal.

In truth they are showing courage and fortitude.

In truth they are allowing natural healing forces to do their slow and painful work.

In truth they are transforming, and transformation requires falling apart before coming back together.

I don’t judge Ms. Sandberg (or anyone else) for using strategies to leap toward the light in order to counter the darkness of grief. Loss, especially untimely loss, is brutal. Loss of innocence for one’s children is almost more than a parent can bear. It can feel like grief is swallowing you whole. I sincerely respect that every one of us has to make it through the intensity of grief’s pain in ways that work for us, and I admire Ms. Sandberg for working so hard to make sure she provides a good life for her kids.

At the same time, I think it’s wise to use caution in pushing for resilience and for overcoming-strategies to be any kind of norm for making it through grief in the long term. Fighting against grief doesn’t work for the long termvery often, at least as far as what I’ve observed in the countless people I’ve helped through this process.

Telling ourselves the story that grief itself is dangerous, instead of being a healthy response to a dangerous situation, actually causes us to be afraid of the grief itself, and then causes grief reactions and emotions to become a source of “bad stress” — the kind of stress that causes health problems. My clients whose grief was shoved aside often show up with depression, anxiety, illness, and shame.

Fortitude Takes Time, But It’s Worth It

Instead, telling ourselves the story that grief reactions are our body’s way of helping us recover from the wound of loss allows us to honor our body’s rhythms and to recruit our nervous system’s responses for healing and restoration.

Telling ourselves the story that overwhelming problems with grief indicate opportunities for healing historic difficulties with managing intense emotions allows us to expand our ability to feel.

When my clients are helped to manage their natural grief reactions and honored for their fortitude in bearing them, I see them grow naturally.

They don’t need to force growth upon themselves prematurely.

Over time, they integrate darkness and light, and emerge into compassion and hard-won wisdom.

More importantly than feeling only joy that’s related to upbeat feelings, they feel enlivened and empowered, knowing that they can welcome and celebrate their full range of emotional experience.

A Conclusion of Compassion

In the end, what I feel for Ms. Sandberg as she uses light-giving strategies to make it out of the darkness, is compassion. Within that feeling of compassion, I find myself wanting to offer her some comfort from this side of my journey through darkness, 25 years after my traumatic loss. It’s a kind of comfort I can’t glean that she’s received from her Silicon Valley cohort:

Ms. Sandberg, if I could, I would give you a hug and say to you in the strongest voice I possess, a voice that comes from the deepest crevices of my soul:

Your children can be okay, even if you are sad a lot, even if you can’t finish mourning quickly.

I can see how earnestly you are working to make sure that their childhoods do not disintegrate. Modeling for them that you can bear your grief and allow it to transform you will help them learn how to do the same. Your efforts will never, ever be lost on them.

Helped to bear their own sorrow, they can have wisdom and a capacity for bearing the pains and joys of life that is beyond their years, and that will have been gained from this high and unchosen price that you and they have been required by life to pay.

It’s even okay if you slow down and let happiness find its way to you and your family slowly and over time. You don’t have to work so hard at striving to be a joyful mom.

I offer you this picture: My son is now 26 years old. He was home for a visit a couple of months ago, and while going through stuff in his room he found a photo album of pictures from the 11-year period when I was raising him alone.(I remarried when he was 12.)

We laughed together as we reminisced about those intense times when it was just the two of us. And then, hugging each other tightly, we burst into tears.

I said through my tears, “It’s so weird. That time when it was just the two of us was the most painful time of my life. Yet it was a tender bubble full of sweetness and a shared reaching for life that I will always treasure. It’s such a strange mix of feelings. It’s stretching my heart wide open.”

He nodded. We sobbed together until we were spent.

This man who is my son has such a strong heart — he can bear the depths of pain and the heights of ecstasy. Nothing is cut off.

He carries scars, and I hate that that’s true. Yet his scars make him wise and beautiful and appreciative of the moments of life like no other 26-year-old I have ever met.

Even if there are days when you can’t find joy, even if there are times when you can’t bounce back, your children can be like this, too, Ms. Sandberg. I promise.

My son died two years ago, aged 23. I tell myself “this will always be part of my life, but it won’t always be all of my life”. Until that time, I hold on as best I can.

Francesca,

I’m so very sorry that you lost your young son. That kind of loss is anguishing and overwhelming. My heart goes out to you. That saying you have is so right. For the first several years of my big loss, the loss was indeed ALL of my life. Now it still hurts, but it has found a place to live within my heart so that it doesn’t fill my whole life. I believe that will happen for you too. It’s very hard, and I send care.

Candyce